The Planetary Boundaries (PBs) framework is essential for the future of sustainable South African agriculture. In the first article of a two-part series, Dr Ndeke Musee, the founder and director of Beyond GenBeta Solutions Pty, explains how it helps farmers and agribusinesses measure whether their production respects ecological limits while staying profitable.

In an address to the Red Meat Abattoir Association Conference, the minister of agriculture, John Steenhuisen, challenged the delegates not only to show that they are producing meat, but also to do it in a way that respects planetary boundaries (PBs) and enhances long-term food system resilience.

Well, this signals a likely policy direction that would require, irrespective of the agricultural product, from farm to fork, to be produced in a way that avoids the transgression of PBs.

That is a mouthful, not just from farmers to retailers, but also to other actors like the financial and logistics sectors. All the actors play essential roles to enhance food production across different value chains – crops, vegetables, horticulture, or livestock. And therefore, their operations should be within the limits defined by the PBs.

In this series, the word “actors” and, unless otherwise specified, refers to role players within the agricultural value chain of the commodity of focus (e.g., farmers, processors, retailers, customers, etc.), auxiliary service providers (e.g., investors, insurers, rating agencies, financial institutions), and regulators.

Then the question is, how can, for example, a product like meat (or any other agricultural product) be produced such that it respects the PBs? Alternatively, what should the product be deemed is produced without transgressing the PBs constraints along its value chain?

To answer this adequately, in a series of articles, I will explain what the PBs framework is and its relevance in agriculture. Two, it’s a business value to all actors from farm to fork. Next, outline an approach for determining whether an agricultural product was produced within the PBs. And, how respecting PBs can support long-term agricultural sustainability, as well as safeguard both social and political order.

Understanding planetary boundaries (PBs)

In brief, operating within PBs can offer multiple benefits, including strengthening food security, enhancing nutrient sufficiency to a growing population, supporting sustainable profitability, and protecting livelihoods.

And, introduce a solution Beyond Genβeta Solutions has developed – the Agricultural Planetary Boundaries Audit Framework (AgPBAF) – a model designed to ensure that South Africa’s agriculture stays productive, resilient, profitable, and environmentally sustainable from farm to fork.

At the core, the model is designed to enable actors across different agricultural products to evaluate and demonstrate that they produce in a way that respects the PBs.

So, what are the PBs? It is a framework that defines limits at which humanity can operate safely without exceeding the stability of the earth system.

Related stories

- How home gardens could transform SA’s food system

- SA food inflation: Why groceries became so expensive

- Climate summit: SA’s food future rests on small-scale farmers

Conditions of the earth system processes include rich biodiversity integrity, stable climate, nitrogen cycling, rich soils (land), and more make up the desirable state essential for food production. For example, in South Africa, to feed the population of 65 million now, and expected to reach 80 million by 2050.

Operating with the PBs is critically important given the limited arable and grazing land, water, and changing climate in our country. At present, science tells us that agriculture is a key driver, among others, towards breaching five of six PBs at the global scale.

Thus, in this first article, I will summarise the origin of agriculture and its historical evolution over time, and therefore, lay the basis of the PBs framework.

Pre-agricultural era

Before the advent of agriculture about 12 000 years ago, food sourcing was through hunting and gathering activities. For example, to meet dietary needs like proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all were sourced from meat and plant products from the wild.

During this period, the human population was very low, defined by small household sizes of mostly three.

However, this state did not last for long.

A gradual shift in food sourcing among hunting and gathering communities emerged. This led to the adoption of agriculture post the last glacial period (LGP), which ended 12 000 years ago. This can be traced as the genesis of farming as the climate became more ambient and favourable, thus, the start of the agrarian revolution.

In The origins of agriculture: an evolutionary perspective. Academic Press, 1984, Ridos highlighted four factors that led societies to begin farming practices.

First, hunting and gathering became less economically rewarding. Resources like wild plant species and animal prey became less abundant. Therefore, food security in terms of access, stability, and sustainability was becoming increasingly untenable.

Secondly, foragers over time had developed tools capable of collecting (including seeds), processing, and storing food. Prior to this period, among the setbacks of foraging were the lack of storage techniques. As a side, food storage remains to this day a key challenge in agriculture, twelfth millennium later in many regions globally, including in South Africa!

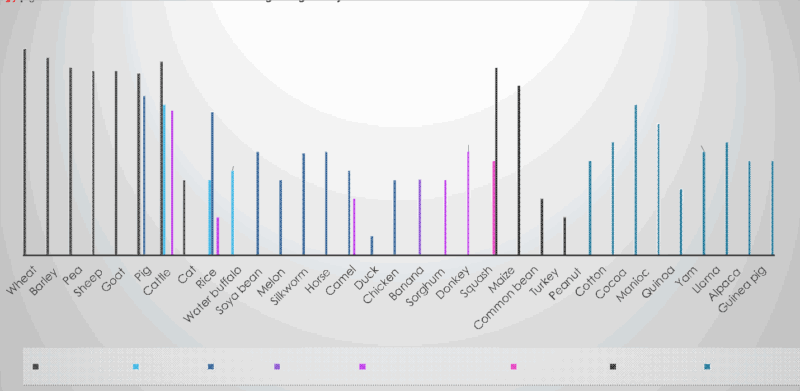

Third, over time due to the accumulation of material resources (tools, weapons, etc.) resulted in reduced mobility, favoured child rearing, and encouraged settlement instead of a nomadic lifestyle. In societies across different regions globally, this marked early signs of the domestication of animals and plants, which led to the birth of the agricultural revolution (see pictorial summary below).

Summary of the earliest signs on the domestication of crops and livestock in different regions across the globe. Data used sourced from Herrera et al., “The agricultural revolutions.” As a chapter in Ancestral DNA, human origins, and migrations (2018): 475-509. Graphical representation by Author: Ndeke Musee

Finally, during the tail end of LGP, climate change led to human migration into new environments. However, these had unfamiliar resources. This forced gatherers to adopt new food sources, hence favouring farming.

Agricultural revolution till 1950s

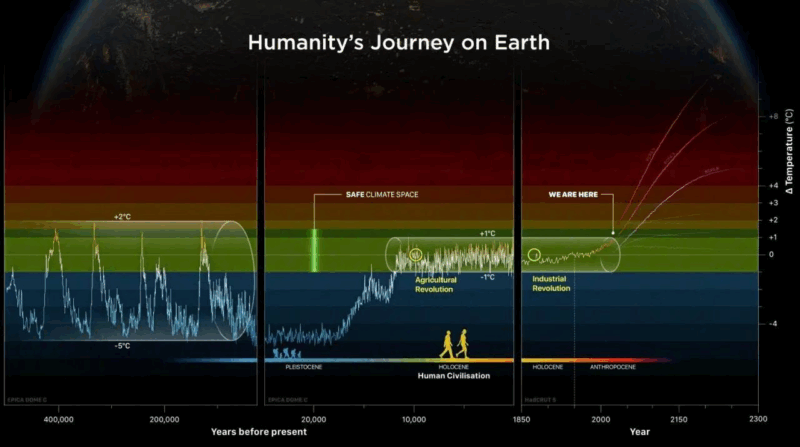

The agricultural revolution took root at what is regarded as the Holocene epoch (also referred to as the Garden of Eden period (GEP)). This is the 12 000-year period after the LGP ended (see figure below). During this period, the earth had relatively stable climatic conditions (e.g., very limited temperature changes, reliable rainfall, and rich biodiversity).

The GEP lasted up to the mid-20th century, where climate change became more apparent, and began to exert increasing adverse impacts on farming-based businesses in many regions across the world, including South Africa.

What were the defining features of GEP?

Humans started having settled life, marked the start of widespread agriculture, and the creation of modern complex civilisations to support life as we know it today. And, over large areas across the globe, hunter and gatherer lifestyles began to be swept away in favour of reliable food supply and settled life.

Pictorial summary of Humanity’s journey on Earth – Human population size and global temperature from 500 000 years before present until 2100. Source: Planetary Health Check 2025 Report.

As a result, the family size increased, followed by high food demand, and as a result, the agricultural villages grew to about two-to-six times larger than those during pre-farming times – all prior to GEP.

Well, this raised challenges too, including the emergence of the elite.

Human civilisation and emergence of social classes

Rising population and advancement in human civilisation resulted in conflicts due to competition related to finite resources like water, fertile lands, and forests. This triggered the genesis of social classes (poor, middle, and elite), and the origins of technological development as a precursor, which gave birth to the Industrial Revolution about 275 years ago.

For the farming communities, in particular, several challenges arose, and three are stated here for illustrative purposes:

- The transition from gatherers to sedentary communities gave birth to wealth and land accumulation. At this time, the elite class began to emerge and dominate their societies, including the farmers who created them.

- From the first point, the elite ventured into politics and commerce, and moved away from agriculture, as the society became highly complex and civilization. The elite allocated themselves the function of controlling and allocating farming land.

- Farming led to an increase in population size, growth of complex societies, and the marked parallel spread of diseases among densely populated communities.

As these developments and advances in agriculture were taking place, they initiated two parallel aspects with divergent pathways. Nonetheless, each ended up causing negative impacts on agricultural productivity.

The expansion of agriculture resulted in water shortages. This led to an increase in: use of irrigation to meet food security and nutrients demand, deforestation to give way for crop production, significant land use change (e.g., soil degradation), a rapid increase in the number of livestock to provide proteins, and rising biodiversity loss for both plants and wild animals.

On the other hand, the development of new technologies led to the expansion of commerce beyond agricultural commodities, enhanced the division of labour, refined social and economic roles, land or property ownership was birthed, and gave rise to the establishment of political and capitalist systems.

Irrespective of the track, they both have had negative and positive impacts on agriculture. As such, both aspects form the foundation of what needs to be considered to develop resilient agriculture of now, and into the future, based on the PBs framework.

READ NEXT: CPA crisis: Non-compliance drags land reform down

Agriculture post-1950s

With a global population of about 2.5 billion by 1950, agricultural systems were increasingly responsible for many negative impacts on nature, whether on air, land, water, biodiversity, or marine resources. The converse is also true. This dual phenomenon is on the rise.

This resulted in agriculture and its associated sectors undergoing numerous fundamental changes, particularly post the 1950s, to meet rising food demand.

For brevity, here are three changes highlighted:

1. Increasingly high food demand and diet shift preferences as a result of the increasing human population, and rising income per capita due to a growing middle class, respectively.

For example, the global middle class by 2020 were some 3.5 billion people with an annual increase estimated at between 140 and 160 million. Seventy per cent of them reside in China and India. This, juxtaposed with 30% of the global population being responsible for over 70% of food’s environmental impacts, justifies a wholesale transformation of our food systems from farm to fork.

Over the same period, however, there has been widespread hunger and malnutrition.

The South African agricultural sector is not immune to such dynamics as relate to shifts in market demands, food insecurity, or nutrient insufficiency. As an example, the country faces steep global market competition as it seeks to gain access to global markets with rising middle-class purchasing power.

2. Agriculture has become pivotal to livelihoods and community wellbeing, and therefore helps lift people out of poverty, totalling 941 000 employed people by the second quarter of 2024 – mostly rural population across the value chain.

3. Lastly, rapid agricultural expansion has led to high consumption of natural capital assets – land, water, and biodiversity – with associated local- to global-scale impacts to the environment (e.g., climate change, pollution, water scarcity, land degradation, and biodiversity loss).

Taken together, these changes form the foundations of differentiated food consumption patterns at national and global scales, and are accompanied by downside effects like detrimental environmental effects, skyrocketing farming costs, steep market competition, and rising demand for sustainably produced foods.

📢 Stand Up, Be Seen, Be Counted

We want to provide you with the most valuable, relevant information possible. Please take a few minutes to complete this short, confidential survey about your farming practices and challenges. Your feedback helps us tailor our coverage to better support the future of agriculture across Mzansi.

Reality check, and future-facing approach

Today, elitism entails both juristic individuals and legal entities – companies. Hart, in an article titled: A natural-resource based view of the firm, back in 1995, observed that ….” few companies have the capacity or market power to alter unilaterally entire sociotechnical systems”. This points to the traditional capitalism paradigm where change is highly challenging to implement, especially as it relates to environmental sustainability.

Peter Bakker, the president of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, in the report Vision 2050: Time to transform. How business can lead the transformations the world needs, pointed out a shift from “doom to gloom” on sustainability. He raised two key points:

“Need for a long-term vision that we can all rally behind: 9+ billion people living well, within planetary boundaries, by mid-century”. This would require “wholesale transformation of everything including how food needs to be produced sustainably and equitably and provide healthy diets”.

And, … a mindset shift and the reinvention of capitalism. The move to a capitalism of true value for all will accelerate the transformation toward 9+ billion people all living well, within planetary boundaries, faster than anything else. A new paradigm on how we define success and determine the enterprise value should emerge as a future-facing approach.

These examples, among many, help us to understand and gain insights as to how we got here. Moreover, the historical perspective is essential to help in framing balanced solutions to address current challenges that face farming-based agribusinesses for now, and beyond.

Key takeaways are:

- The “why” to adopt the PBs approach as a means to shape: how we farm, process and distribute food, protect the environment, enhance sustainable profitability, and support livelihoods in agricultural regions.

- Agriculture is the bedrock of civilisation, but at the same time led to population growth estimated as 6 million at around 10 000 years ago to about 8.25 billion by October 2025. Today, it is among the key drivers responsible for breaching five of six PBs at the global scale as society seeks to guarantee food security and nutrient sufficiency.

- To realise the full benefits of PBs across the South African agricultural value chains requires an understanding of the science, policy, and efforts necessary to operationalise the framework.

- Future–looking and transformation approaches on how we measure success, evaluate business value now form the new capitalism paradigm essential to transform society to a liveable planet within the PBs.

- Working collaboratively among multiple actors across a value chain, irrespective of agricultural product, is central to respecting the constraints imposed by PBs for a liveable future.

- Dr Ndeke Musee is the founder and director of Beyond GenBeta Solutions Pty (BGβS) and holds a doctorate in chemical engineering science from Stellenbosch University. BGβS has developed a beta version: Agricultural Planetary Boundaries Audit Framework (AgPBAF), designed to assess environmental sustainability across the crops, horticulture, vegetables, and livestock value chains from farm to fork, considering the unique South African context. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Food For Mzansi.

READ NEXT: Masogas’ backyard garden booms into 140-ha crop blueprint