Farming in South Africa has entered a new era, one where seed technology, precision agriculture, and scientific innovation are no longer optional but essential tools for success. With growing demands for higher yields, resilient crops, and sustainable practices, understanding the choices available to farmers has never been more critical.

Dr Godfrey Kgatle, plant pathologist and research coordinator at Grain SA, offers insight into how traditional breeding, hybrids, genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and new breeding techniques (NBTs) are transforming agriculture. From improving farm profitability to protecting crops against diseases and pests, these innovations are shaping the future of farming.

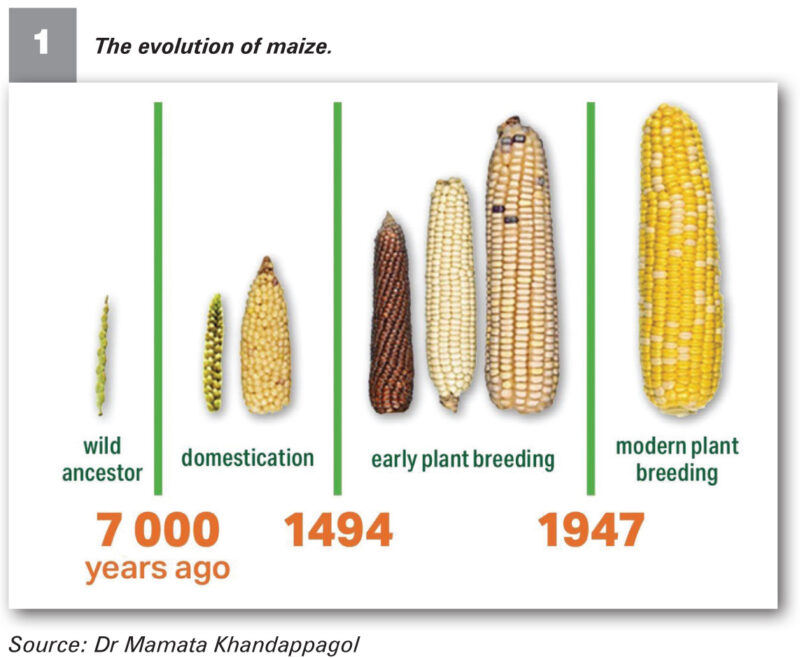

Kgatle describes how maize and other staple crops have evolved over thousands of years through domestication and breeding, moving from wild plants to today’s high-performing commercial varieties.

He highlights the remarkable yield gains achieved over the past century, as detailed in his Grain SA article.

“From breeding a cob into hybrids and then into GMOs, the average national maize yield per hectare in 2025 has reached six tonnes. Over the last 100 years, yields have increased tenfold, from 0.6 to six tonnes per hectare.

“This growth is due to several factors: the introduction of mechanisation, fertilisers, hybrids, GMOs, and most recently, precision agriculture. The adoption of precision agriculture represents the latest significant leap in productivity,” he notes.

These gains reflect a combination of scientific progress and improved farming systems, showing how technology has consistently lifted productivity.

Traditional breeding, hybrids, GMOs, and NBTs each offer unique advantages. By understanding these options, farmers can make informed decisions that strengthen their operations and contribute to national food security.

Understanding the main seed types currently available

Kgatle emphasises that different seed types offer different advantages, and farmers must understand these differences to make informed choices.

Related stories

- New Plant Improvement Act to boost SA crop quality

- Maize: Choosing the right varieties for local conditions

- Hybrid seeds: Tips for optimising maize yields

- Getting started with sorghum farming

Open-pollinated varieties (OPVs)

OPVs offer seed-saving flexibility but come with limited yield potential.

“The OPVs, open-pollinated varieties, in the 1920s, when we started doing our first records, those were the crops that were being used. At the end of the season, the farmer is actually able to harvest the grain, keep a bit for himself, and then use the rest or sell it. The drawback is that it has a yield cap,” Kgatle says.

Hybrid seeds

Hybrids break through the OPV yield ceiling, giving farmers higher productivity, though they must be purchased annually for maximum performance.

“Then there was an introduction of hybrids. They allowed for that yield cap to then get breached, doubling in yield. It’s something a farmer has to then grapple with for themselves. Do I save my seeds and yield two tonnes, or do I buy a new batch of seeds every year, but then I double my income?”

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs)

GMOs offer built-in protection against pests, diseases, and drought, critical benefits in a climate-stressed environment.

“The GMOs have then come in and really supported farmers in various ways. Genetically modified crops can protect from insects, pests and diseases. It also enables crops to actually then during drought periods be able to be protected as well. Yield protection and climate resilience, that’s what GMO actually gives us.”

New breeding techniques (NBTs)

Kgatle described NBTs as a leap forward in speed, efficiency, and genetic precision.

Science has advanced tremendously, but breeding a single cultivar remains a costly and time-consuming process, often running into billions. Kgatle explains that new breeding techniques leverage a deep understanding of maize genetics, allowing breeders to identify the markers for traits such as yield or drought tolerance and directly modify plants to express these traits.

While it doesn’t reduce the process to instant results, it enables breeders to achieve outcomes much faster than the traditional 20-year timeline.

He reassures the public that these technologies are strictly monitored. “All of these are guided under policies, by the way. It’s not something that a naughty scientist, that you see in movies, comes in and manipulates. There are policies and guidelines across the world on how these things can work and be managed.”

NBTs allow breeders to respond faster to emerging challenges, including climate pressures and new diseases. He notes that this is critical as the country’s population grows, with projections estimating a rise to 75 million.

Kgatle explains that NBTs are still in the process of being introduced in South Africa, primarily due to the rigorous policy and regulatory frameworks that ensure farmers, consumers, and seed companies are protected.

However, he says this careful approach is a privilege, allowing South African farmers to be confident that any cultivar released has undergone stringent testing to guarantee quality, adaptability, and safety. While the regulatory process may slow the immediate introduction of NBTs, it ensures that once available, these innovations are both reliable and safe.

📢 Stand Up, Be Seen, Be Counted

We want to provide you with the most valuable, relevant information possible. Please take a few minutes to complete this short, confidential survey about your farming practices and challenges. Your feedback helps us tailor our coverage to better support the future of agriculture across Mzansi.

Benefits of NBTs for farmers

Enhanced profitability

Farmers invest significantly in production, ranging from R19 000 to R27 000 per hectare on dryland crops. Traditional OPVs often have yield caps, limiting economic returns. Hybrids increase yields and profits, but NBTs offer the potential to accelerate this advantage. Higher yields and improved resilience directly translate into better returns.

Disease and pest resistance

NBTs allow precise breeding for traits like disease and pest resistance. For example, recent ear rot outbreaks caused by fusarium or diplodium could be mitigated by targeting specific genetic markers.

As Kgatle puts it, “NBTs become a more direct and more focused approach as compared to traditional breeding; instead of testing tens of thousands of crops [for their genetic markers], you only test those that you are interested in because you [already] know what their genetics look like.”

He explains that when a new disease emerges, NBTs allow breeders to rapidly develop crops that are resilient, resistant, or tolerant to the threat.

Climate resilience

With the increasing unpredictability of weather and frequent droughts, NBTs offer a tool to breed crops that can withstand adverse conditions:

“When a new disease comes in, NBTs can enable the breeders to quickly develop a crop that can be resilient, resistant, or tolerant to a disease,” he says.

This ensures continuity in production, helping farmers and the nation maintain food security even under challenging climatic conditions.

Choice and flexibility

Kgatle emphasises that choice is central to successful farming.

“We need to always have a choice. If a farmer is comfortable based on their farming operation with OPVs, I fully encourage that. Choice must always stay, and it will always depend on the end user, who is the farmer at the end of the day.”

NBTs do not replace traditional seeds or hybrids; they expand options, allowing farmers to select the varieties that best suit their operations, region, and market needs.

The value of seed access and choice

Farmers benefit when they have access to a broad selection of seed varieties tested for local conditions.

“We do national cultivar trials on an annual basis. In these trials, more than 150 cultivars are tested across the country on their adaptability to a particular place. To a farmer, that is a big win. It enables them to have a choice, depending on their production system,” Kgatle says.

With this information, farmers can choose varieties that best fit their climate, soil, management style, and risk appetite.

READ NEXT: Farming within limits: Understanding planetary boundaries