South Africa’s farmers sit at the centre of a food system that has been reshaped by some of the most dramatic price pressures in a generation. From global shocks that sent fertiliser and grain markets soaring, to climate volatility and exchange-rate swings that affected imports and exports, each factor has left its mark on farms and households.

To understand how these forces have unfolded and what they mean for producers and consumers alike, Food For Mzansi draws on data from the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP), sourced from Statistics South Africa, to trace the story behind food prices since 2021.

By analysing BFAP’s detailed tracking of the Thrifty Healthy Food Basket alongside broader CPI movements, we provide an evidence-based view of the forces shaping demand, supply pressures, and long-term resilience across South Africa’s food system.

Factors that shape food prices in SA

(Scroll to see the full timeline)

Related stories

- Record maize crop bodes well for food inflation

- FMD: SA’s meat future hinges on biosecurity overhaul

- Climate summit: SA’s food future rests on small-scale farmers

- Grain and oilseed markets: Tariffs shake up global trade

Agricultural trade economist Buhlebemvelo Dube said food inflation cannot be understood without recognising how interlinked global and domestic systems have become. He noted that higher food prices are not only a function of harvest volumes, but also energy costs, logistics constraints, biosecurity threats, and exchange rate volatility, all of which directly shape retail prices.

“When global markets experience shocks, South Africa absorbs those shocks faster than before because our value chains are deeply integrated into international supply systems. That means local households feel the impact long before any policy response can catch up.”

Buhlebemvelo Dube

He highlighted that low-income families are disproportionately affected because they spend the largest share of their income on food. “Even small spikes in staples such as maize meal, bread, potatoes, or eggs translate into immediate hardship. The ceiling keeps rising, but wages are not rising at the same pace.”

Dube argued that this is why tracking food affordability, not just inflation, is essential to understanding real household vulnerability, particularly during consecutive years of climate-related disruptions and global uncertainty.

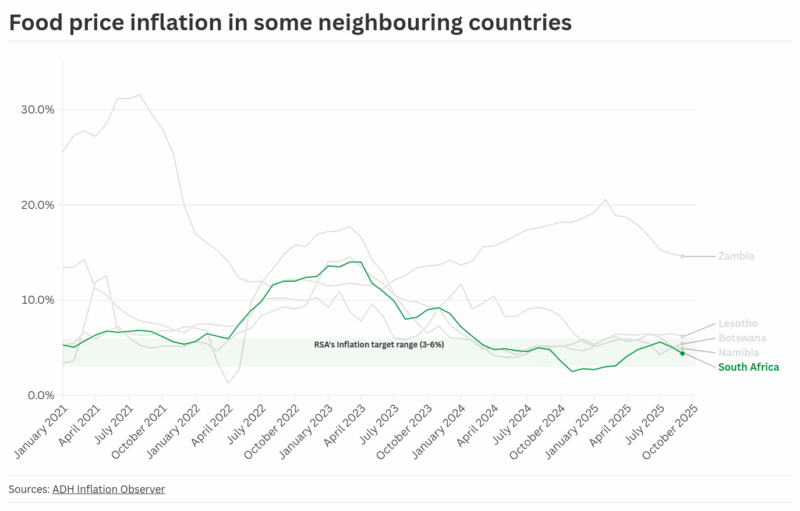

It is not just South Africa that has been impacted by food inflation. Across the southern African region, countries experienced very different inflation journeys:

- South Africa saw a clear rise in prices through 2022 before conditions gradually stabilised in the years that followed.

- Botswana recorded the sharpest spike of all the countries, but its inflation cooled quickly thereafter.

- Lesotho consistently faced higher price pressures than its neighbours and continued to feel the strain long after others had normalised.

- Namibia followed a more moderate path, with a gentler climb and a delayed easing compared to the rest of the region.

- In contrast, Tanzania maintained one of the most stable inflation environments throughout the period.

Overall, southern African countries experienced far greater volatility, while Tanzania remained comparatively steady.

Some relief over the past few months

According to Paul Makube, senior agricultural economist at First National Bank, South Africa’s food inflation continued to slow in October, easing to 3.9% year-on-year. Makube explains that the easing was largely driven by softer prices in vegetables, fruits and nuts, sugar and confectionery, and meat, which more than offset mild increases in cereals, dairy, oils, and fats.

Monthly food inflation also remained in deflation for the third consecutive month.

Vegetable prices fell sharply, driven by steep declines in staples such as potatoes and onions. Raw commodity prices remain exceptionally low, particularly for maize and wheat, signalling a likely reversal in cereal inflation.

Meat inflation also cooled after recent record highs, with Makube noting that meat inflation had slowed. However, he said, “Continued foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) induced disruptions to trade remain a concern” despite ongoing vaccination efforts.

The SARB’s most recent Monetary Policy Committee statement offers a wider context on the economic landscape. Governor Lesetja Kganyago highlighted that while the global economy has faced turbulence and shifting trade patterns, growth has been more resilient than anticipated, noting concerns over potential bubbles linked to the AI investment boom.

Domestically, economic growth appears steadier than the previous year, bolstered by stronger household spending and increasing employment.

What to expect moving forward

Headline inflation picked up slightly to 3.6% in October, mainly due to meat, vegetables, and fuel, but the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) expects the pressure to be temporary. “Recent outcomes have undershot our forecasts slightly. We are on track to deliver 3% inflation over the medium term,” said Lesetja Kganyago, governor of the SARB.

Against this backdrop, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC ) reduced the policy rate by 25 basis points on the 21st of November 2025 to 6.75%. The SARB also confirmed its shift to a new point target for inflation of 3% ±1%, emphasising: “We want to be at 3%,” Kganyago added.

With a stronger rand that recently fell below R17/US$, along with improved seasonal conditions and declining producer prices, Makube anticipates that food inflation is likely to show a further downward trajectory over the medium term.

This article is a collaboration between Food For Mzansi and OpenUp, supported by Africa Data Hub.

READ NEXT: Maintaining organic matter: Key steps to boost soil health