After weeks of mounting tension over foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreaks, South Africa has reached a historic milestone in animal health. The Agricultural Research Council (ARC) has released the country’s first locally produced FMD vaccine.

This landmark achievement is said to strengthen South Africa’s capacity to protect its livestock industry, safeguard food security, and reduce reliance on imported vaccines.

FMD is one of the most contagious viral diseases affecting cloven-hoofed animals, including cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. Outbreaks across the country are currently devastating local economies, disrupting trade, and threatening the livelihoods of farmers. The current outbreak has heightened urgency, making the availability of a locally manufactured vaccine, even at a small scale, a game-changer for the agricultural sector.

A game-changer for herd health

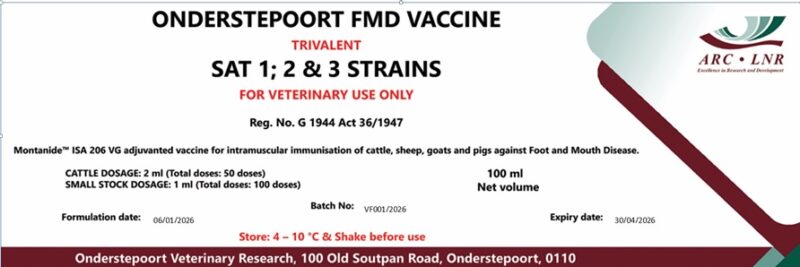

Developed and produced entirely by ARC scientists and technical experts using local infrastructure, the vaccine represents the culmination of two decades of research and government investment. Registered as a stock remedy under Act 36/1947 (Reg. No. G1944), the first batch of 12 900 multi-strain doses meets stringent quality, safety, and efficacy standards.

Local production offers critical advantages: faster response times during outbreaks, improved alignment with region-specific virus strains, and stronger supply chain control. It also builds national scientific capacity, contributes to skills development, and creates jobs in biotechnology and veterinary manufacturing.

For farmers, the vaccine promises reliable access and renewed confidence in herd health. This is key for sustaining productivity and protecting access to both domestic and international markets. Consumers benefit too, through a stable supply of safe and affordable animal-derived food products.

In a release, the ARC says its milestone is also a demonstration of South Africa’s commitment to biosecurity and animal disease preparedness. It highlights the strategic value of investing in domestic vaccine production to prevent and control transboundary animal diseases.

Looking ahead, the ARC has completed the design of a new production facility that will enhance vaccine self-reliance in line with the national disease control strategy. Once operational, the facility is expected to further secure South Africa’s livestock industry and strengthen its agricultural economy.

Related stories

- Steenhuisen quits DA leadership, pledges to end FMD

- An FMD-free future: Pipe dream or reality?

- A commercial farmer’s dismay: Steenhuisen faces FMD storm

- Govt steps up FMD fight with mass cattle vaccination plans

The production of South Africa’s first locally manufactured FMD vaccine was led by Dr Faith Peta alongside a dedicated team of ARC scientists and technical experts. The team includes Virginia Mahlangu, Kabelo Tlaka, Tumelo Ratopola, Thando Veto, Lucas Phaahla, Lucas Mabena, Gabriel Makhubela, and Bernard Matlou, whose combined expertise in veterinary science, biotechnology, and vaccine production made this milestone possible.

South Africa’s livestock industry has been on high alert as foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) spreads aggressively across eight of the country’s nine provinces, severely disrupting the commercial value chain. Analysts warn that the outbreak has already caused significant economic damage and affected animal welfare, with many producers facing potential financial disaster. The emotional toll on farmers and dairy producers has been immense, heightening tensions across the sector.

Vaccine monopoly sparks industry tension

The ARC’s announcement follows weeks of warnings from experts about the urgent need for a coordinated, scientifically rigorous response to FMD outbreaks, underscoring the importance of clear leadership and controlled vaccine deployment.

Agbiz chief economist Wandile Sihlobo and Professor Johann Kirsten note, “Everyone seems to have become an overnight expert on the disease, while there are only a few experts and veterinarians in South Africa who have successfully managed previous FMD outbreaks.”

This misinformation has complicated efforts to implement coordinated, scientifically grounded responses, including vaccination programs. Amid this uncertainty, calls for clear leadership have grown louder.

Sihlobo and Kirsten note the need for a centralised, technically rigorous approach, writing that “it is also time for the department to get its act together and work collaboratively with those who can manufacture, distribute, and apply vaccines.”

While private veterinarians can assist with administering vaccines, the procurement, monitoring, and distribution must be strictly managed by the state to maintain international standards and protect South Africa’s FMD-free status, argues Sihlobo and Kirsten.

Free State Agriculture, together with key industry partners, has formally challenged the state’s exclusive control over FMD vaccines, demanding that farmers be allowed to procure and administer private vaccines under the supervision of state and private veterinarians.

Francois Wilken, FSA president, warned that the state’s monopoly and delays are placing livestock farmers at immediate risk of financial collapse. He said the situation is also jeopardising food security. Wilken noted, “If no favourable response is received by the deadline, further legal action will be considered.” He framed the move as a necessary step to protect constitutional rights, support the survival of the industry, and safeguard the broader economy.

READ NEXT: An FMD-free future: Pipe dream or reality?